© firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com

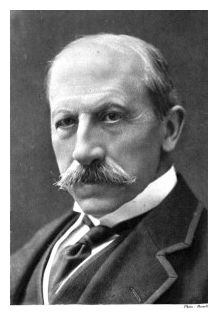

Viscount Alfred Milner, unquestioned leader of the Secret Elite.

In 1916, when the British government set up the Dardanelles Commission, they turned first to the most important member of the Secret Elite, Viscount Alfred Milner. Prime Minister Asquith and conservative leader, Bonar Law, both asked him to be its chairman, [1] but Milner turned the offer down in favour of more immediate work with Lord Robert Cecil at the Foreign Office. [2] Anyone could supervise a whitewash. Alfred Milner's influence want well beyond that of a commission chairman and he could ensure the conclusion without the need for his personal involvement. They turned to another friend and associate of the Secret Elite, Evelyn Baring, Lord Cromer, who accepted the position knowing full well that 'it will kill me'. [3] And kill him it did. He died in January 1917 and was replaced by Sir William Pickford.

Others volunteered willingly. The position of Secretary to the Commission was taken by barrister Edward Grimwood Mears, who agreed to the post provided he was awarded a knighthood. [4] He had previously served on the Bryce Committee which falsified reports and generated volumes of lies about the extent of German atrocities in Belgium. [5] The British Establishment trusted Mears as a reliable placeman. Maurice Hankey, Cabinet Secretary and inner-circle member of the Secret Elite [6] 'organised' the evidence which politicians presented to the Commission. He rehearsed Lord Fisher's evidence, and coached Sir Edward Grey, Herbert Asquith and Lord Haldane. [7] Asquith insisted that War Council minutes be withheld and thus managed to cover up his own support for the campaign. Churchill and Sir Ian Hamilton collaborated on their evidence and planned to blame the disaster on Lord Kitchener. [8] Unfortunately for them, that strategy sank in the cold North Sea when Kitchener was drowned off the coast of Orkney in 1916, and was henceforth confirmed for all time as a great national hero; an untouchable.

Churchill informed the Commission that Vice-Admiral Sackville-Carden's telegram (in which he set out a 'plan' for a naval attack) was the most crucial document of all, [9] but there is no acknowledgement in the Commission's findings that Churchill had duped Carden into producing a 'plan' or had lied when telling him that his 'plan' had the overwhelming support of 'people in high authority.' [10] Every senior member of the Admiralty had advised Churchill that a naval attack on its own would fail, but he made no reference to that and scapegoated the ineffective Carden. General Hamilton conveniently added that the only instructions he had received from Kitchener before his departure was that 'we soldiers were clearly to understand that we were string number two. The sailors said they could force the Dardanelles on their own, and we were not to chip in unless the Admiral definitely chucked up the sponge.' [11]

© firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com

General Sir Ian Hamilton

Criticisms in the Commission's interim report in March 1917 were 'muted and smudged'. The War Council should have sought more advice from naval experts; the expedition had not succeeded but 'certain important political advantages' had been secured. In the final report, delayed until the peace of 1919, criticism was again polite, bland and vague. 'The authorities in London had not grasped the true nature of the conflict' and 'the plan for the August offensive was impractical.' [12] Stopford received a mild reprimand. Major-General De Lisle suggested that politicians were trying to pin the blame on the soldiers. The Commission ostensibly investigated the campaign's failings, but effectively suppressed criticism, concealed the truth and neither wholly blamed nor vindicated those involved.

Far more important than covering up individual culpability, the greatest fear of the London cabal was that, should the report come close to the truth, it would irrevocably damage imperial unity. Gallipoli had served to lock Australia more firmly into the British Imperial embrace. Before the final report was published, Hamilton warned Churchill that it had the potential to break up the Empire if it 'does anything to shatter the belief still confidently clung to in the Antipodes, that the expedition was worth while, and that 'the Boys' did die to a great end and were so handled as to be able to sell their lives very dearly. ...If the people of Australia and New Zealand feel their sacrifices went for nothing, then never expect them again to have any sort of truck with our superior direction in preparations for future wars.' [13] This was the crux of the matter, even in 1919. The truth would threaten the unity of the Empire, run contrary to the Anzac mythology and expose the lies that official histories were presenting as fact. Prior to the final report, Hamilton wrote again to Churchill that the Commission's chairman, Sir William Pickford, should be warned about the imperial issues at stake. He, Churchill, should 'put all his weight on the side of toning down any reflections which may have been made.' [14] In other words, it had to be a whitewash. The warning was heeded. The following year, Pickford was raised to the peerage as Baron Sterndale. It was ever thus for those who served the Secret Elite.

The truth about Gallipoli was buried and pliant historians have ensured that it stayed that way for nearly a century.

Surely a whitewash was impossible given that the Dardanelles Commission included Andrew Fisher, former Australian Prime Minister and then High Commissioner in London? But he too had bought into the big lie and made no attempt to question or refute its conclusions.

© firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com

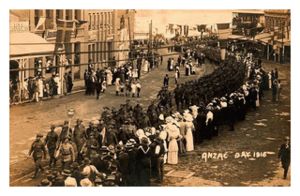

Anzac Day Commemorative Parade.

According to historian Les Carlyon, the Australian government did not welcome an inquiry into the disaster because 'the Anzac legend had taken hold and Australia didn't want officialdom spoiling the poetry.' [15] The 'poetry', the 'heroic-romantic' myth, was created in the first instance by writers such as Charles Bean, Henry Nevison and John Masefield who glorified the Anzac sacrifice within the myth of Gallipoli. [16] Masefield's effusive cover-up stated, 'I began to consider the Dardanelles Campaign, not as a tragedy, nor a mistake, but as a great human effort, which came more than once, very near to triumph ...That the effort failed is not against it; much that is most splendid in military history failed, many great things and noble men have failed. ...This failure is the second grand event of the war; the first was Belgium's answer to the German ultimatum.' [17] Of Suvla Bay, where thousands died from thirst and dehydration, Masefield made the astonishing assertion: 'The water supply of that far battlefield, indifferent as it was, at the best, was a triumph of resolve and skill unequalled yet in war.' [18]

This British apologist and purveyor of nauseating historical misrepresentation was rewarded with gushing praise from Lord Esher, member of the Secret Elite's inner-core, together with a Doctorate of Literature by Oxford University, the Order of Merit by King George V and the prestigious post of Poet Laureate.

The British, French and Anzac troops who perished at Gallipoli are portrayed by mainstream historians as heroes who died fighting to protect democracy and freedom, not as ordinary young men duped by a great lie. Barely mentioned are the quarter million dead or maimed Ottoman soldiers who defended Gallipoli and the sovereignty and freedom of their homeland against aggressive, foreign invaders. The myths and lies that saturate the Gallipoli campaign are particularly prevalent in the Antipodes. 'No-one could pass through the Australian education system without becoming aware of Gallipoli, but few students realise that the Anzacs were the invaders. Even after all these years, the Anzac legend, like all legends, is highly selective in what it presents as history.' [19] And it is a well preserved and repeatedly inaccurate account that is force-fed to these impressionable youngsters.

© firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com

Turkish Memorial at Lone Pine erected after the Allied withdrawal in December 1915.

Commemoration should respectfully educate people about what really happened at Gallipoli, but strategic analyst and former Australian Defence Force officer James Brown writes angrily about a cycle of jingoistic commemoration rather than quiet contemplation, with individuals, groups and organisations cashing in on Anzac Day. 'A century after the war to end all wars, Anzac is being bottled, stamped and sold. ...the Anzac industry has gone into hyperdrive. ...What started as a simple ceremony is now an enormous commercial enterprise. ...Australians are racing to outdo one another with bigger, better, grander and more intricate forms of remembrance.' Even the Australian War Memorial has devised an official "Anzac Centenary Merchandising Plan" to capitalise on "the spirit."' [20] The myth has been rebranded to mask the pain of the awful reality of Gallipoli. The emaciated, dehydrated victims have been turned into the bronzed heroes of Greek mythology.

A number of Australian historians remain deeply concerned about the relentless militarisation of Australian history, and how the commemoration of Gallipoli has been conflated with a mythology of white Australia's creation and the 'manly character' of its citizens. That mythology is submerging the terrible truth about why so many were sacrificed and has become so powerful and pervasive that to challenge it risks the charge of inexcusable disrespect for the dead. 'To be accused of being "anti-Anzac" in Australia today is to be charged with the most grievous offence.' [21] A few brave historians have dared to voice their deep disquiet.

Professors Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds believe that Australian history has been 'thoroughly militarised', and their aim is 'to encourage a more critical and truthful public debate about the uses of the Anzac myth.' Dissent, they say, is rarely tolerated and 'to write about what's wrong with Anzac today is to court the charge of treason.' Anzac Day has 'long since ceased to be a day of solemn remembrance and become a festive event, celebrated by backpackers wrapped in flags, playing rock music, drinking beer and proclaiming their national identity on the distant shores of Turkey.' [22] Their forefathers were duped into volunteering a century before at a cost they never foresaw. It is clear that many of those young Australians who travel en-masse to the shores of Gallipoli every April have also been duped. Should there not be a moral outrage against these obscene celebrations; a moral outrage that these young people have been so misled by the Gallipoli myth that the irony of guzzling beer on the shores where their forefathers died from thirst and dehydration is lost on them.?

© firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com

Anzac Day 1916.

Professor Lake revealed that after a radio broadcast, she was subjected to personal abuse and accusations of disloyalty. Harvey Broadbent, another Australian historian who questions the myth, has also been subject to similar comments by some fellow Gallipoli historians that 'has come uncomfortably close to abuse.' Like us,

Broadbent proposes that 'it was the intention of the British and French governments of 1915 to ensure that the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli Campaign would not succeed and that it was conceived and conducted as a ruse to keep the Russians in the war and thus the continuation of the Eastern Front.' [23] Exactly. Their aim was to keep Russia in the war but out of Constantinople. And they succeeded, but at a terrible cost.

The heroic-romantic myth, so integral to the cult of remembrance, has survived, perpetuated by compliant historians and politicians. As James Brown has written, Gallipoli and the Anzac sacrifice, is like a magic cloak which 'can be draped over a speech or policy to render it unimpeachable, significant and enduring.' [24] Norman Mailer pointed out that 'Myths are tonic to a nation's heart. Once abused, however, they are poisonous.'

© firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com

Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, 1915.

Gallipoli was a lie within the lie that was the First World War, and peddling commemoration mythology as truth is an insult to the memory of those brave young men who were sacrificed on the merciless shores of a foreign country. The Australian government is outspending Britain on commemoration of the First World War by more than 200 per cent, and commemorating the Anzac centenary might cost as much as two-thirds of a billion dollars. Just as in Britain, the Government of Australia seeks to be the the guardian of public memory, choreographing commemoration into celebration. [25] Nothing attracts politicians more than being photographed, wrapped in the national flag, outbidding each other in their public display of patriotism.

These hypocrites ritually condemn war while their rhetoric gestures in the opposite direction. [26] The War Memorial in Sydney's Hyde Park proudly exhorts, 'Let Silent Contemplation Be Your Offering', yet the deafening prattle of political expediency mocks the valiant dead with empty words and lies. Don't be fooled.

Those young men died at Gallipoli not for 'freedom' or 'civilisation', but for the imperial dreams of the wealthy manipulators who controlled the British Empire. They died horribly, deceived, expendable, and in the eyes of the power-brokers, the detritus of strategic necessity.

Please remember that when you remember them.

References:

[1] Milner Papers, Bonar Law to Milner, 25 July 1916.

[2] A M Gollin, Proconsul in Politics, pp. 350-1.

[3] Roger Owen, Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul, pp 388-9.

[4] Jenny Macleod, Reconsidering Gallipoli, p. 27.

[5] see previous blog; The Bryce Report...Whatever Happened To the Evidence? 10 September 2014.

[6] Carroll Quigley, The Anglo-American Establishment, p. 313.

[7] Stephen Roskill, Hankey, p.294.

[8] Macleod, Reconsidering Gallipoli, pp. 28-9.

[9] Martin Gilbert, Winston S Churchill, p. 248.

[10] Alan Moorehead, Gallipoli, p. 40.

[11] Martin Gilbert, Winston S Churchill, p. 347.

[12] L A Carlyon, Gallipoli p. 646.

[13] Macleod, Reconsidering Gallipoli, p. 33.

[14] Ibid.

[15] L A Carlyon, Gallipoli, pp. 645-7.

[16] Macleod, Reconsidering Gallipoli, p. 4.

[17] John Masefield, Gallipoli p.2.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Kevin Fewster, Vecihi Bagram, Hatice Bagram, Gallipoli, The Turkish Story, pp. 10-11.

[20] James Brown, Anzac's long Shadow, The Cost of Our National Obsession, pp. 17-20.

[21] Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, What's Wrong with Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History, p. xxi.

[22] Ibid., pp. vii-viii.

[23] Harvey Broadbent, Gallipoli, One Great Deception? http://ab.co/1DOrtoO

[24] James Brown, Anzac's Long Shadow, p 29.

[25] Ibid., pp. 19-22.

[26] Lake and Reynolds, What's Wrong With Anzac?, p. 8.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service - if this is your content and you're reading it on someone else's site, please read the FAQ at http://bit.ly/1xcsdoI.